Feb 16 2016

Light can be used to control the transport of proteins from the cell nucleus with the aid of a light-sensitive, genetically modified plant protein. Biologists from Heidelberg University and the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) working in the field of optogenetics have now developed such a tool. The researchers, under the direction of Dr. Barbara Di Ventura and Prof. Dr. Roland Eils, employed methods from synthetic biology and combined a light sensor from the oat plant with a transport signal.

This makes it possible to use external light to precisely control the location and hence the activity of proteins in mammalian cells. The results of this research were published in the journal “Nature Communications”.

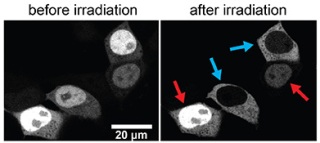

Microscopy images of human embryonic kidney cells in culture. The cells were genetically modified to produce a glowing protein, which was linked to the new optogenetic tool (the LOV2-NES hybrid). Cells irradiated with a blue laser beam (blue arrows) show an efficient nuclear export of the protein. Non-irradiated cells (red arrows) show a constitutively nuclear localisation of the protein. Source: Dominik Niopek

Microscopy images of human embryonic kidney cells in culture. The cells were genetically modified to produce a glowing protein, which was linked to the new optogenetic tool (the LOV2-NES hybrid). Cells irradiated with a blue laser beam (blue arrows) show an efficient nuclear export of the protein. Non-irradiated cells (red arrows) show a constitutively nuclear localisation of the protein. Source: Dominik Niopek

Eukaryotic cells are characterised by the spatial separation between the cell nucleus and the rest of the cell. “This subdivision protects the mechanisms involved in copying and reading genetic information from disruptions caused by other cellular processes such as protein synthesis or energy production,” explains Prof. Eils, Director of Heidelberg University's BioQuant Centre and head of the Bioinformatics Department at Ruperto Carola and the DKFZ. Proteins and other macromolecules pass through the nuclear pore complex into and out of the cell nucleus in order to control a number of biological processes.

While smaller proteins passively diffuse through the nuclear pores, larger particles must latch onto so-called carrier proteins to make the trip. Usually short peptides on the protein surface signal the carriers that the protein is ready for transport. This signal is known as the nuclear localization signal (NLS) for transport into the nucleus, and the nuclear export sequence (NES) for transport out of the nucleus. “Artificially inducing the import or export of selected proteins would allow us to control their activities in the living cell,” says Dr. Di Ventura, group leader in Prof. Eils' department.

The Di Ventura lab has specialised in optogenetics, a relatively new field of research in synthetic biology. Optogenetics combines the methods of optics and genetics with the goal of using light to turn certain functions in living cells on and off. To this end, light-sensitive proteins are genetically modified and then introduced into specific target cells, making it possible to control their behaviour using light.

The recently published work reporting an optogenetic export system builds upon previous studies by other working groups investigating the LOV2 domain, which originally comes from the oat plant. In nature, this domain acts as a light sensor and, among other things, assists the plant in orienting to sunlight. The LOV2 domain fundamentally changes its three-dimensional structure as soon as it comes into contact with blue light, explains Dominik Niopek, primary author of the study.

The property of light-induced structure change can now be used specifically to synthetically control cellular signal sequences – like the nuclear export signal (NES). Dominik Niopek first developed a hybrid LOV2-NES protein made up of the LOV2 domain of the oat and a synthetic nuclear export signal. In the dark state, the signal is hidden in the LOV2 domain and not visible to the cell. Light causes the structure of the LOV2 to change, which renders the NES visible and triggers the export of the LOV2 domain from the nucleus.

“In principle, the hybrid LOV2-NES protein can be attached to any cellular protein and used to control its export from the nucleus using light,” says Prof. Eils. The researcher and his team demonstrated this using the p53 protein, a member of the family of cancer-suppressing proteins that monitor cell growth and prevent genetic defects during cell division. According to Roland Eils, p53 is switched off in a number of aggressive tumours by harmful genetic mutations that allow the tumour cells to reproduce uncontrollably.

Using the LOV2-NES protein, the Heidelberg researchers were able to control the export of p53 from the nucleus using light to control its gene regulatory functions. “This new ability to directly control p53 in living mammalian cells has far-reaching potential to explain its complex function in depth. We hope to uncover new clues about the role of possible defects in p53 regulation related to the development of cancer,“ says Dr. Di Ventura.

The researchers are convinced that their new optogenetic tool can also be used to make important discoveries on the dynamics of protein transport and its influence on cell behaviour. “Our research is only as good as our tools,“ says Prof. Eils. “The development of innovative molecular tools is therefore the key to understanding basic cellular functions as well as the mechanisms that cause illness.“