Feb 20 2008

Standard microscopy and visible light imaging techniques cannot peer into the dark and murky centers of dense-liquid jets, which has hindered scientists in their quest for a full understanding of liquid breakup in devices such as automobile fuel injectors.

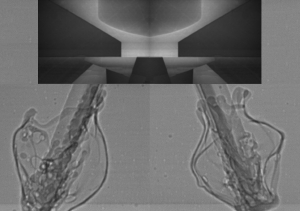

The liquid breakup of a high-density stream from a fuel injector can easily be seen using an X-ray technique developed at Argonne National Laboratory. The technique could lead to better and cleaner fuel injectors.

The liquid breakup of a high-density stream from a fuel injector can easily be seen using an X-ray technique developed at Argonne National Laboratory. The technique could lead to better and cleaner fuel injectors.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory have developed a technique to peer through high-speed dense liquids using high-energy X-rays from Argonne's Advanced Photon Source (APS).

"The imaging contrast is crisp and we can do it orders of magnitude faster than ever before," Argonne X-ray Science Division physicist Kamel Fezzaa said.

Fuel injector efficiency and clean combustion is dependent on the best mixture of the fuel and air. To improve injector design, it is critical to understand how fuel is atomized as it is injected. However, standard laser characterization techniques have been unsuccessful due to the high density of the fuel jet near the injector opening. Scientists have been forced to study the fuel far away from the nozzle and extrapolate its dispersal pattern. The resulting models of breakup are highly speculative, oversimplified and often not validated by experiments.

"Research in this area has been a predicament for some time, and there has been a great need for accurate experimental measurement," Fezzaa said. "Now we can capture the internal structure of the jet and map its velocity with clarity and confidence, which wasn't possible before."

Fezzaa and his colleagues, along with collaborators from the Mayo Clinic and Visteon Corp. developed a new ultrafast synchrotron X-ray full-field phase contrast imaging technique and used it to reveal instantaneous velocity and internal structure of these optically dense sprays. This work is highlighted in the Advance Online Publication of the journal Nature.

A key to the experiment was taking advantage of the special properties of the X-ray beam generated at the APS. Unlike hospital x-rays, the synchrotron x-rays are a trillion times brighter and come in very short pulses with durations as little as 100 nanoseconds.

"The main challenge that our team had to overcome was to be able to isolate single x-ray pulses and use them to do experiments, and at the same time protect the experimental setup from being destroyed by the overwhelming power of the full x-ray beam," Fezzaa said.

Their new technique has the ability to examine the internal structure of materials at high speed, and is sensitive to boundaries. Multiphase flows, such as high-speed jets or bubbles in a stream of water, are ideal systems to study with this technique. Other applications include the dynamics of material failure under explosive or ballistic impact, which is of major importance to transportation safety and national security, and material diffusion under intense heat.

The research was funded by DOE's Office of Basic Energy Sciences as part of its mission to foster and support fundamental research to expand the scientific foundations for new and improved energy technologies and for understanding and mitigating the environmental impacts of energy use, and by a laboratory-directed research and development grant.