Oct 29 2009

PAIR Technologies, a start-up company established by University of Delaware researchers and a former DuPont scientist, is preparing to commercialize a high-precision detector -- a planar array infrared spectrograph -- that can identify biological and chemical agents in solids, liquids, and gases present at low levels, in less than a second.

The revolutionary technology holds promise in multiple applications, ranging from the early detection of diseases, to monitoring for chemical weapons and environmental pollutants, to enhancing quality-control efforts in manufacturing processes.

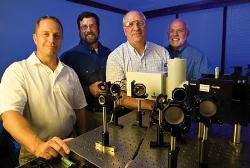

The business partners involved in PAIR Technologies with their high-precision detector, which holds promise in numerous medical, military, environmental, and industrial applications. From left, Dan Frost, Scott Jones, Bruce Chase, and John Rabolt.

The business partners involved in PAIR Technologies with their high-precision detector, which holds promise in numerous medical, military, environmental, and industrial applications. From left, Dan Frost, Scott Jones, Bruce Chase, and John Rabolt.

John Rabolt, the Karl W. and Renate Böer Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at UD, and his students invented and patented the technology in 2001.

Rabolt and Bruce Chase, who recently retired from DuPont as a research chemist, founded the company in 2005.

Their partners in the company include Scott Jones, professor of accounting and director of the Venture Development Center in UD's Lerner College of Business and Economics, and Dan Frost, who received his master of business administration degree from UD in 2008.

The University of Delaware owns the patents for the technology, which are under exclusive license to PAIR Technologies, and has taken a small equity position in the company.

"PAIR Technologies offers an analytical tool with the potential to contribute significant benefits to society through a wide array of medical, military, environmental, and industrial applications," says David Weir, director of UD's Office of Economic Innovation and Partnerships.

"The company grew out of UD innovation and is a model for how federal, state, and University partners can work together to advance economic development," Weir notes. "These are the kinds of high-tech economic partnerships the University of Delaware wants to develop, and we will be looking more aggressively at opportunities like this in the future."

According to Weir, this is only the second time in the University's history that it has taken a small equity position in a UD start-up company. The first was ET International, a computer technology and software company founded by Guang Gao, Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

The idea for PAIR Technologies actually was spawned in a UD graduate course, "High-Tech Entrepreneurship," which Rabolt and Jones co-teach. Students explore selected UD patented technologies in the course and then do market analyses to assess their commercialization potential. The planar array infrared technology consistently rose to the top.

"Most technology has about a 30-year cycle. Then something comes along to disrupt it, change it," Rabolt says. "We think we have that next-generation technology -- beyond the current market leader, Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy."

The company has been steadily developing with federal, state, and University support, the researchers say.

"The whole thing is a partnership -- you can't do it alone," Jones notes. "We've written the grant proposals and won Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) and Small Business and Innovation Research (SBIR) grants from the National Science Foundation. A 'bridge' grant from the Delaware Economic Development Office also was very helpful, and we've gotten invaluable assistance from experienced alumni, including Allan Ferguson, Barry Yerger, and David Freschman," Jones says.

OEIP and the Delaware Small Business Development Center, which is a new and critical component of OEIP, also has provided the company with a variety of help and services, from intellectual property protection to marketing assistance, according to Jones.

"The environment is much more business friendly now at the University of Delaware," Rabolt adds. "Statistically, only one in 20 start-ups will make it. Yet the ones that are successful are enormously successful. These kinds of opportunities also help attract high-quality faculty and students to UD," he notes.

Planar Array Infrared (PAIR) Spectroscopy

Spectroscopy is a technique for measuring the concentration or amount of a given material by measuring how well that material absorbs or transmits light.

While it would take the current technology, which was designed more than 30 years ago -- a Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectrograph -- tens of minutes to chemically identify the petroleum in a major oil spill, for example, PAIR Technologies' new instrument could provide the molecular fingerprint in one second or less, hastening cleanup efforts, Rabolt says.

When a sample is placed into the current FT-IR spectrograph for analysis, the instrument divides the infrared light source into two beams that reflect off both a fixed and a moving mirror. Two separate experiments must be run for every analysis -- one with the sample, and one without. The latter accounts for any "background interference" from the environment, which must be mathematically reconciled. Additionally, the sample chamber must be purged with nitrogen gas to displace any water vapor.

The PAIR Technologies instrument has no moving parts. It relies on a focal plane array, commonly used in medical imaging, which consists of a cluster of light-sensing pixels at the focal plane of a lens to receive the optically dispersed infrared light. As a result, the PAIR Technologies instrument provides a direct reading in under a second.

"This is a rugged replacement for the existing technology, taking it out of the lab and into the field," Chase says. "Our instrument has no moving parts. It's durable, compact, and portable -- you can carry it out to your local stream or use it in a doctor's or dentist's office."

Recognized internationally as leaders in the field of spectroscopy, Rabolt and Chase are award-winning scientists who were good-natured competitors for years until they joined forces in 2000 to begin developing their new analytical tool.

The two collectively have more than 65 years in scientific research, with a significant portion in industry -- Chase recently retired after 33 years at DuPont, and Rabolt worked for 20 years at IBM before joining the UD faculty in 1996.

A new vision for diagnosing eye diseases

Besides environmental monitoring and even a potentially remote way to sample toxins to aid soldiers and hazardous materials (hazmat) responders, the scientists see applications in industry to help maintain and improve manufacturing processes, ensuring, for example, the purity of pharmaceutical drugs or the thickness of paints or polymer coatings.

The detector also may bring new medical applications into focus.

For Rabolt, that became apparent when he visited his ophthalmologist's office and was diagnosed with developing cataracts.

"They've been developing for years, but now they are big enough to scatter light, and that's the only way to diagnose cataracts currently," he says. "If we can 'spectroscopically' detect a small amount of protein in a person's teardrops, we may be able to provide a new diagnostic tool for detecting cataracts early on and potentially many other eye diseases."

For Dan Frost, his three-credit graduate course a few summers ago as a UD graduate student expanded his horizons rapidly into the world of business, where he is now chief operating officer of PAIR Technologies.

"It's very rewarding to be involved in something that's going to really benefit society," Frost says. "Initially, we will do the manufacturing here," he notes of the company's office suite in Delaware Technology Park. "We plan on doing the assembly locally. That's a win-win for us and for Delaware."