Aug 9 2007

By combining the capabilities of several telescopes, teams of scientists, including University of Massachusetts Amherst astronomers, have spotted extremely bright galaxies hiding in the distant, young universe.

They are the most luminous and prolific galaxies seen at that great distance, churning out stars at a rate 1,000 times greater than that of the Milky Way.

The findings prompt new questions about star formation and highlight the promise of instruments that detect infrared and submillimeter waves. The results will be published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Shrouded in dust and gas and thus not visible to optical telescopes, the galaxies were initially spotted with the Astronomical Thermal Emission Camera (AzTEC) on the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii. The camera, developed by an international group of scientists led by UMass Amherst's Grant Wilson, discovered several hundred previously unseen galaxies that were bright at millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths, frequencies that lie between what optical telescopes and radio telescopes are designed to observe.

Wilson, UMass Amherst's Min Yun and a team of astronomers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, made follow-up observations of the seven brightest galaxies in an area of the sky studied by the Cosmic Evolution Survey (COSMOS). The Smithsonian's Submillimeter Array pinpointed the exact location of each galaxy, allowing the team to confirm that the source was a single galaxy and not a blend of several fainter galaxies.

Once precise locations were known, the astronomers searched for the galaxies in images from previous observations made with the Hubble Space Telescope, the Spitzer Space Telescope, and the Very Large Array as part of the overall COSMOS survey. Even Hubble's powerful vision did not detect the galaxies, confirming that they are shrouded in dust that blocks visible light. Spitzer could penetrate the dust and detect the stars directly. The Very Large Array detected only the two closest galaxies.

By combining these measurements, the astronomers showed that five of the seven AzTEC galaxies are located at redshifts greater than 3, which corresponds to a time when the universe was less than 2 billion years old. Astronomers believe the universe is roughly 13.7 billion years old.

"We know that star formation was happening at a pretty good clip and then tapered off about 7 billion years ago, when the universe was about half its present age," says UMass Amherst's Wilson. "The rates that these early bright galaxies are forming stars suggest that we've been underestimating the rate of early star formation by not properly accounting for the dimming due to dust in these systems."

The galaxies are located about 12 billion light-years away, and existed when the universe was less than 2 billion years old. Astronomers think that smaller, dimmer galaxies were much more common in the early universe because it takes time for galaxies to form and grow.

"It's a real surprise to find galaxies that massive and luminous existing so early in the universe," said astronomer Giovanni Fazio of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, a lead author on the paper. "We are witnessing the moment when the most massive galaxies in the universe were forming most of their stars in their early youth."

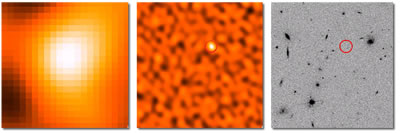

Credit: UMass Amherst/CfA/COSMOS - A bright but dusty and extremely distant galaxy (left) discovered by the AzTEC camera. The high resolution Smithsonian's Submillimeter Array pinpointed the galaxy (center) which is not detected by the Hubble Space Telescope (right). Observations show that this galaxy existed when the universe was less than 2 billion years old.

Credit: UMass Amherst/CfA/COSMOS - A bright but dusty and extremely distant galaxy (left) discovered by the AzTEC camera. The high resolution Smithsonian's Submillimeter Array pinpointed the galaxy (center) which is not detected by the Hubble Space Telescope (right). Observations show that this galaxy existed when the universe was less than 2 billion years old.

The galaxies' large infrared brightness indicates that they are forming new stars rapidly, probably due to collisions and mergers, says Wilson. But it's hard to tell without more data, he adds. Future studies that image more of the galaxies discovered by AzTEC should reveal much more about what triggers star formation in early galaxies.

"To really understand these objects we need to examine hundreds of galaxies, not seven," says Wilson. "Galaxies are complicated beasts—we want to look at as many as we can and figure out their sociology—who's hanging out with whom and what different groups are doing."