Nov 10 2008

From the Tour de France to NASCAR, competitors and fans know that speed is only part of the equation. Strategy -- and the ability to use elements like aerodynamic drafting, which makes it easier to follow closely behind a leader than to be out in front -- is also critical.

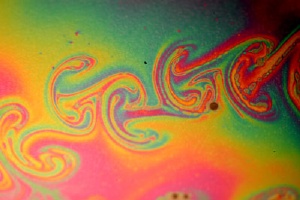

Pattern created by a zebrafish swimming through water. (A thin layer of oil coats the water's surface). Leif Ristroph's research on flapping flags could provide insight into how fish and other animals move through and interact with their fluid surroundings. Credit: Leif Ristroph.

Pattern created by a zebrafish swimming through water. (A thin layer of oil coats the water's surface). Leif Ristroph's research on flapping flags could provide insight into how fish and other animals move through and interact with their fluid surroundings. Credit: Leif Ristroph.

But in some cases, drafting happens in reverse: It's the leader of a pack who experiences reduced drag, while the followers encounter more resistance -- and have to expend more energy to keep up.

In research published in the Nov. 7 issue of Physical Review Letters (Vol. 101: No. 194502), Cornell fourth-year physics graduate student Leif Ristroph and New York University researcher Jun Zhang used a simple tabletop experiment to show that two or more flexible objects in a flow -- flags flapping in the wind, for example -- experience drag very differently than rigid objects in a similar flow.

The findings could help biologists understand a variety of phenomena, including why animals like fish and birds travel in groups.

"It's counterintuitive," said Ristroph. "People who have studied schooling fish and flocking birds always postulate that they flock because the ones downstream can save energy, and the guy who's at the front has to work harder. Here's a case where that gets turned on its head."

To test the effects of a flowing fluid on flexible objects, Ristroph created a thin film of soapy water -- the beginning of a giant soap bubble -- stretched between two fishing lines and constantly refreshed with a flow of water from the top. Into the membrane, he inserted pieces of thin rubber (the flags) -- attached to perpendicular wire "flagpoles."

To measure the forces on the flags as water flowed past them, Ristroph attached small mirrors -- actually microscope cover slips -- to the far ends of the "flagpoles." As the flags flapped in the flow, the slightly flexible poles moved correspondingly -- and by shining a laser light on the mirrors, Ristroph could see the movements magnified and traced on a far wall.

He also used optical interferometry -- a technique based on the way light waves interfere with each other -- to measure the fluid flow around the flapping flags.

Instead of finding that the front flag took the brunt of the drag and following flags experienced less resistance, he found that for two flags close together, the front flag flapped less and thus experienced less drag -- even relative to a single flag without a follower. For the follower, he found the reverse: The flag oscillated more and experienced correspondingly more drag.

"That was completely unexpected," Ristroph said. Additional experiments with multiple flags and different spacing showed that the effect is consistent for closely spaced objects and drops off as the space between them increases.

The effects aren't fully understood, Ristroph said. "It appears that the follower is sort of confining the flow at the trailing edge of the leader, so it feels like he can't flap as hard; [and therefore] the amplitude of the leader is reduced." For the follower, the oscillations of the leader likely cause a resonating effect, increasing the follower's flapping and thus its drag.

"This is now like a two-way conversation, where the fluid talks to the object, and the object talks back," Ristroph said.

"Simulating this is very difficult," he added. "The theory and the simulation really cannot handle how to deal with the flow and an object that has flexibility.

"You often have to do the experiment," he said. "And when you do the experiment you can get something that is counterintuitive."

Ristroph performed the research during a summer fellowship at NYU through the Interdisciplinary Graduate Training in Nonlinear Systems program, which is funded by the National Science Foundation.