Image credit: Christopher Strock / Penn State

There are intimate relationships that take place in the rhizosphere, where plant roots and soil biota come together, but it can be quite tricky to see exactly what kind of interactions occur there.

Throughout the root-soil system the population of organisms that dwell there can be abundantly diverse and include various species such as fungi, nematodes (worms), and arthropods (insects). Understanding what kinds of exchanges take place between plant roots and soil organisms can be advantageous to developing the next-generation of agricultural systems. What’s more, is that it is believed that the interchanges that take place between root anatomy and the organisms in the soil are insufficiently researched.

So, there are many ways in which the soil organisms can interact with the root systems of plants and include interactions such as mutualism, commensalism, herbivory, and parasitism. In fact, understanding the latter could be the key to a future in cultivation of crops in the future that could be more resistant and resilient to disease.

Thus, it is thought to be crucial that research in this field improves. This is where an imaginative use of a custom laser system comes in, one that was first developed in Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences eight years ago.

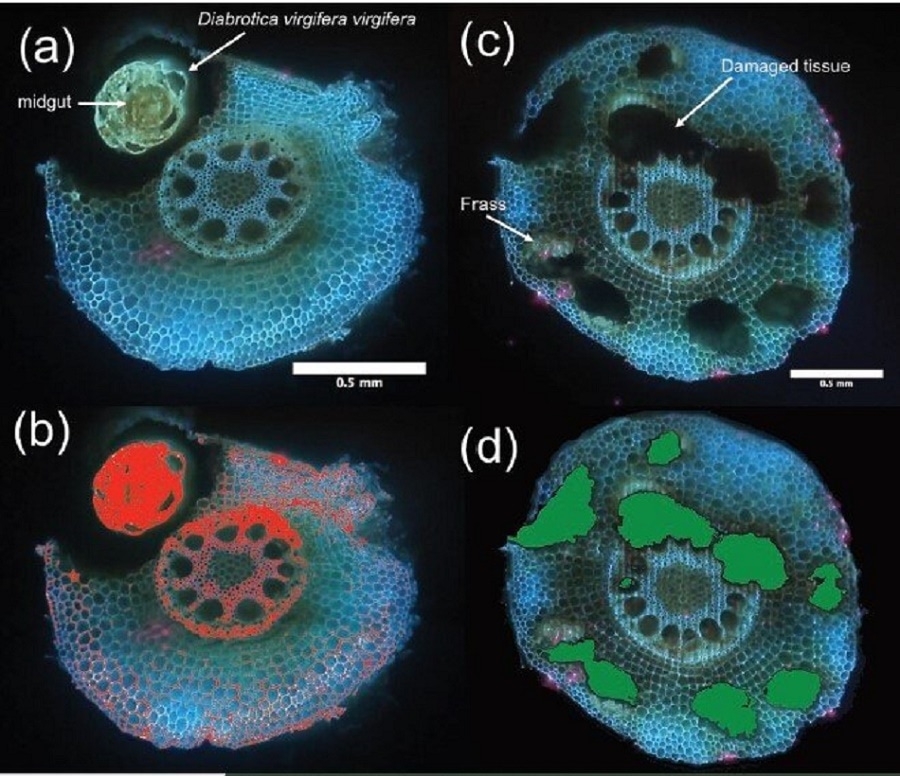

The laser system, known as laser ablation tomography (LAT), cuts through the plant root sample under observation and then researchers can measure the light spectra emitted by the various cells that have been spliced. Once the laser has cut the various samples the tissues of the cells will show distinct patterns of RGB light based on their chemical composition.

LAT not only can provide us with a novel perspective of interactions among roots and soil organisms, but we also are able to process many root samples in a short period of time with this technology.

Johnathan Lynch, Distinguished Professor of Plant Science, Penn State

The increased throughput rate of the system demonstrated in the study also enables research teams to overcome a major hurdle due the fact, “Researchers who are interested in conducting genetic studies and running breeding programs to develop crops that are more resistant to soil pathogens," added Lynch. Whilst, it is thought the organisms that move between the rhizomatic root systems can have significant impact on crop yields there is also an interest in any reciprocal effects that take place between root and organism.

Fungi, notably arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, are a pervasive species that are associated with “>80% of terrestrial plant species” as referenced in the study. This group of fungi is essential components to the life-force of plant systems as they enable the exchange of nutrients via Mycorrhizal Symbiosis between co-existing plants. This multiplicity benefits all as plants or crops are supplied with vital resources as well as sustaining the fungi and are subterranean biodiversity, not to mention the surface benefits that come from a thriving flora.

Throughout the study, the team utilized their unique LAT system for the analysis of corn roots affected by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. These corn root samples were also colonized by western corn rootworm. Researchers also obtained samples of barley roots parasitized by cereal cyst nematode, and bean roots that had been feasted on by Fusarium fungi. This resulted in differing signals of RGB light spectra that enabled the team to categorize various tissues and other anatomical features.

Christopher Strock, Postdoctoral Scholar at Penn State who was co-author of the study noted that, “LAT serves as an excellent tool to conduct large, quantitative screenings to characterize genetic control of root anatomy and interactions with soil organisms.”

The system allows the team to view the samples in three dimensions which allows for the quantification of the volume and distribution of fungal colonization, areas that incur damage, feeding sites, and any other weakened tissues.

The goal of Lynch, Strock and their team is to generate further research that will eventually lead to further advances in both plant sciences and agriculture. Looking at both the destructive implications of parasitic organisms as well as the more mutualistic benefits of fungi species such as AMF, perhaps it may be possible to yield stronger resilient crops as well as encouraging cultivation in strenuous conditions. Furthermore, it could help stimulate a wider field of research, "By demonstrating the versatility of the technology, we pave the way for other scientists to use it to address questions about roots and soil interaction at the anatomical level,” said Lynch.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.