Jul 26 2016

An electronic device that could lead to smaller, low-power memory chips can now be controlled and probed by light, as revealed by research from KAUST.

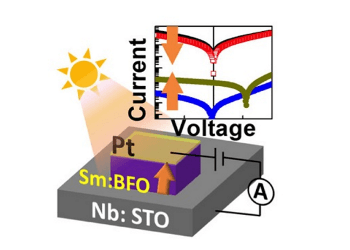

A ferroelectric tunnel junction made from platinum (Pt) samarium-doped bismuth iron oxide (Sm:BFO) and niobium-doped strontium titanate (Nb:STO) is a memory device that can be controlled by both electricity and light. (Credit: © 2016 KAUST)

A ferroelectric tunnel junction made from platinum (Pt) samarium-doped bismuth iron oxide (Sm:BFO) and niobium-doped strontium titanate (Nb:STO) is a memory device that can be controlled by both electricity and light. (Credit: © 2016 KAUST)

The device is a ferroelectric tunnel junction (FTJ) that contains a thin layer of a ferroelectric material sandwiched between two electrodes. Ferroelectric materials are intrinsically polarized so that negative electrical charge concentrates on one side of the layer and positive charge clusters on the opposite side. Applying an electric field flips this polarization, and the two states can represent the "1"s and "0"s of binary data. The device crucially does not need power to retain this data.

Tom Wu of from the KAUST Material Science and Engineering program and colleagues created an FTJ containing a film of ferroelectric samarium-doped bismuth iron oxide (SBFO) that was just three to nine nanometers thick1. One electrode was made of platinum and the other was niobium-doped strontium titanate (NSTO), a light-sensitive semiconductor.

Electrons can sometimes tunnel through a very thin ferroelectric layer—a quantum mechanical process that allows them to skip across an energy barrier to create a current. In one of its polarization states, SBFO has a low tunneling electroresistance (TER) that allows electrons across. However, in the other polarization state, the team found that its TER is 100,000 times larger, which prevents electron tunneling. This is the largest change in TER ever seen for a FTJ, providing an unambiguous way to read its polarization state.

Exposing the device to ultraviolet light reduced this high TER ten-fold, as light makes NSTO more conducting, which assists electron tunneling.

“This means that we could acquire a total of four electronic states corresponding to polarization direction (left or right) and illumination condition (dark or light),” noted Wu. “Each electronic state can be used to store one bit of information. By introducing light illumination into FTJs, we double the data storage density, which could be very promising for future technology.”

Although the TER difference between the two states gradually wanes, the team calculated that there would still be a significant distinction after 10 years, making it suitable for long-term data storage.

It took about 10 microseconds to switch the device from one state to the other—faster than conventional flash memory but lower than some other forms of advanced memory.

“One immediate goal of our research is to make these FTJ devices smaller and faster,” said Wu. “In addition, we will work to enhance the light detection capability of such ultrathin junctions.”