Nov 11 2015

Researchers at North Carolina State University have developed techniques that can be used to create ideal geometric phase holograms for any kind of optical pattern - a significant advance over the limitations of previous techniques. The holograms can be used to create new types of displays, imaging systems, telecommunications technology and astronomical instruments.

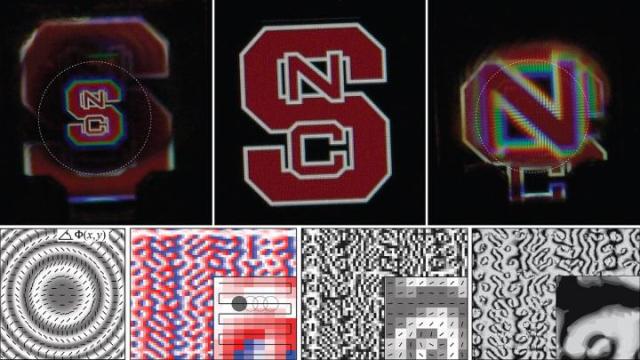

Here are three images of the NC State logo as viewed through a geometric phase hologram, in this case a lens, where each corresponds to one of the three possible wavefronts. Bottom Row: Illustrations, simulation, and microscope picture showing the liquid crystal orientation created by the light patterning techniques reported in the paper, showing a lens profile (left image) and a far-field hologram profile (right three images). Credit: Michael Escuti

Here are three images of the NC State logo as viewed through a geometric phase hologram, in this case a lens, where each corresponds to one of the three possible wavefronts. Bottom Row: Illustrations, simulation, and microscope picture showing the liquid crystal orientation created by the light patterning techniques reported in the paper, showing a lens profile (left image) and a far-field hologram profile (right three images). Credit: Michael Escuti

A geometric phase hologram is a thin film that manipulates light. Light moves as a wave, with peaks and troughs. When the light passes through a geometric phase hologram, the relationship between those peaks and troughs is changed. By controlling those changes, the hologram can focus, disperse, reorient or otherwise modify the light.

An ideal geometric phase hologram modifies the light very efficiently, meaning that little of the light is wasted. But ideal geometric phase holograms can also produce three different, well-defined "wavefronts" - or transformed versions of the light that passes through the thin film.

"We can direct light into any one or more of those three wavefronts, which allows us to use a single ideal geometric phase hologram in many different ways," says Michael Escuti, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at NC State and corresponding author of a paper on the work.

Previously, researchers were only able to make ideal geometric phase holograms in a limited set of simple patterns, curtailing their usefulness for new applications. This is because making these holograms involves orienting molecules or structures at a scale smaller than the wavelength of light.

"We've come up with two ways of making ideal geometric phase holograms that are relatively simple but allow us to control the orientation of the molecules that ultimately manipulate the light," Escuti says.

First, the researchers use lasers to create a high-fidelity light pattern, either by taking advantage of how waves of light interfere with each other, or by using a tightly focused laser to scan through a pattern - much like a laser printer.

A photoreactive substrate records the light pattern, with each molecule in the substrate orienting itself depending on the polarization of the light it was exposed to. To understand this, think of a beam of light as a wavy string, traveling from left to right. That string is also vibrating up and down - creating wiggles are that are perpendicular to the direction the string is traveling. Controlling the orientation angle of the light's linear polarization just means controlling the direction that the wave is wiggling.

The pattern that is recorded on the substrate then serves as a template for a liquid crystal layer that forms the finished hologram.

"Using these techniques, we're able to create ideal geometric phase holograms in nearly any pattern," Escuti says. "Theoretically, there are patterns that are too small for us to make, but we've been able to make patterns for every practical application we've addressed so far - from astronomical instruments to art installations.

"This work gave us a great deal of insight into controlling the spatial properties of light waves," Escuti says. "We're now exploring how we can better manipulate the spectrum of light waves. For example, we're determining how we can handle visible light and infrared light differently within a single hologram."

Escuti is also working with his company, ImagineOptix Corporation, to develop new applications and improve existing technologies that may benefit from higher efficiency thin-films.