Sep 16 2015

Researchers at the RIKEN Brain Science Institute in Japan have developed a new technique for creating transparent tissue that can be used to illuminate 3D brain anatomy at very high resolutions. Published in Nature Neuroscience, the work showcases the new technology and its practical importance in clinical science by showing how it has given new insights into Alzheimer's disease plaques.

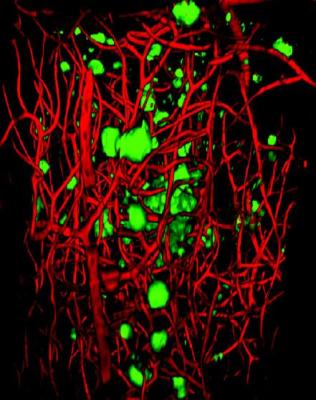

This is a 3-D visualization of Aâ plaques (green) and blood vessels (red) in a region of cerebral cortex from a 20-month-old AD model mouse. Credit: RIKEN

This is a 3-D visualization of Aâ plaques (green) and blood vessels (red) in a region of cerebral cortex from a 20-month-old AD model mouse. Credit: RIKEN

"The usefulness of optical clearing techniques can be measured by their ability to gather accurate 3D structural information that cannot be readily achieved through traditional 2D methods," explains lead scientist Atsushi Miyawaki. "Here, we achieved this goal using a new procedure, and collected data that may resolve several current issues regarding the pathology of Alzheimer's disease. While Superman's x-ray vision is only the stuff of comics, our method, called ScaleS, is a real and practical way to see through brain and body tissue."

In recent years, generating see-through tissue--a process called optical clearing--has become a goal for many researchers in life sciences because of its potential to reveal complex structural details of our bodies, organs, and cells--both healthy and diseased--when combined with advanced microscopy imaging techniques. Previous methods were limited because the transparency process itself can damage the structures under study.

The original recipe reported by the Miyawaki team in 2011--termed Scale--was an aqueous solution based on urea that suffered from this same problem. The research team spent 5 years improving the effectiveness of the original recipe to overcome this critical challenge, and the result is ScaleS, a new technique with many practical applications.

"The key ingredient of our new formula is sorbitol, a common sugar alcohol," reveals Miyawaki. "By combining sorbitol in the right proportion with urea, we could create transparent brains with minimal tissue damage, that can handle both florescent and immunohistochemical labeling techniques, and is even effective in older animals."

The new technique creates transparent brain samples that can be stored in ScaleS solution for more than a year without damage. Internal structures maintain their original shape and brains are firm enough to permit the micron-thick slicing necessary for more detailed analyses.

"The real challenge with optical clearing is at the microscopic level," said Miyawaki, "In addition to allowing tissue to be viewable by light microscopy, a practical solution must also ensure accurate tissue preservation for effective electron microscopy."

On these tests, ScaleS passed with flying colors providing an optimal combination of cleared tissue and fluorescent signals, and Miyawaki believes that the quality and preservation of cellular structures viewed by electron microscopy is unparalleled.

The team has devised several variations of the Scale technique that can be used together. By combining ScaleS with AbScale--a variation for immunolabeling--and ChemScale--a variation for fluorescent chemical compounds--they generated multi-color high-resolution 3D images of amyloid beta plaques in older mice from a genetic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease developed at the RIKEN BSI by Takaomi Saido team.

After showing how ScaleS treatment can preserve tissue, the researchers put the technique to practical use by visualizing in 3D the mysterious "diffuse" plaques seen in the postmortem brains of Alzheimer's disease patients that are typically undetectable using 2D imaging. Contrary to current assumptions, the diffuse plaques proved not to be isolated, but showed extensive association with microglia --mobile cells that surround and protect neurons.

Another example of ScaleS's practical application came from examining the 3D positions of active microglial cells and amyloid beta plaques. While some scientists suggest that active microglial cells are located near plaques, a detailed 3D reconstruction and analysis using ScaleS clearing showed that association with active microglial cells occurs early in plaque development, but not in later stages of the disease after the plaques have accumulated.

"Clearing tissue with ScaleS followed by 3D microscopy has clear advantages over 2D stereology or immunohistochemistry," states Miyawaki. "Our technique will be useful not only for visualizing plaques in Alzheimer's disease, but also for examining normal neural circuits and pinpointing structural changes that characterize other brain diseases."