Mar 11 2015

Computers that function like the human brain could soon become a reality thanks to new research using optical fibres made of speciality glass.

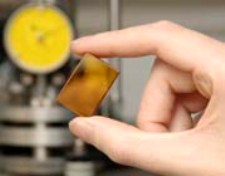

Chalcogenide glass sample

Chalcogenide glass sample

The research, published in Advanced Optical Materials, has the potential to allow faster and smarter optical computers capable of learning and evolving.

Researchers from the Optoelectronics Research Centre (ORC) at the University of Southampton, UK, and Centre for Disruptive Photonic Technologies (CDPT) at the Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore, have demonstrated how neural networks and synapses in the brain can be reproduced, with optical pulses as information carriers, using special fibres made from glasses that are sensitive to light, known as chalcogenides.

The project, funded under Singapore’s Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) Advanced Optics in Engineering programme, was conducted within The Photonics Institute (TPI), a recently established dual institute between NTU and the ORC.

Co-author Professor Dan Hewak from the ORC, says: “Since the dawn of the computer age, scientists have sought ways to mimic the behaviour of the human brain, replacing neurons and our nervous system with electronic switches and memory. Now instead of electrons, light and optical fibres also show promise in achieving a brain-like computer. The cognitive functionality of central neurons underlies the adaptable nature and information processing capability of our brains.”

In the last decade, neuromorphic computing research has advanced software and electronic hardware that mimic brain functions and signal protocols, aimed at improving the efficiency and adaptability of conventional computers.

However, compared to our biological systems, today’s computers are more than a million times less efficient. Simulating five seconds of brain activity takes 500 seconds and needs 1.4 MW of power, compared to the small number of calories burned by the human brain.

Using conventional fibre drawing techniques, microfibers can be produced from chalcogenide (glasses based on sulphur) that possess a variety of broadband photoinduced effects, which allow the fibres to be switched on and off. This optical switching or light switching light, can be exploited for a variety of next generation computing applications capable of processing vast amounts of data in a much more energy-efficient manner.

Co-author Dr Behrad Gholipour explains: “By going back to biological systems for inspiration and using mass-manufacturable photonic platforms, such as chalcogenide fibres, we can start to improve the speed and efficiency of conventional computing architectures, while introducing adaptability and learning into the next generation of devices.”

By exploiting the material properties of the chalcogenides fibres, the team led by Professor Cesare Soci at NTU have demonstrated a range of optical equivalents of brain functions. These include holding a neural resting state and simulating the changes in electrical activity in a nerve cell as it is stimulated. In the proposed optical version of this brain function, the changing properties of the glass act as the varying electrical activity in a nerve cell, and light provides the stimulus to change these properties. This enables switching of a light signal, which is the equivalent to a nerve cell firing.

The research paves the way for scalable brain-like computing systems that enable ‘photonic neurons’ with ultrafast signal transmission speeds, higher bandwidth and lower power consumption than their biological and electronic counterparts.

Professor Cesare Soci said: “This work implies that ‘cognitive’ photonic devices and networks can be effectively used to develop non-Boolean computing and decision-making paradigms that mimic brain functionalities and signal protocols, to overcome bandwidth and power bottlenecks of traditional data processing.”