Jun 16 2009

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have created bright, stable and bio-friendly nanocrystals that act as individual investigators of activity within a cell.

These ideal light emitting probes represent a significant step in scrutinizing the behaviors of proteins and other components in complex systems such as a living cell.

Labeling a given cellular component and tracking it through a typical biological environment is fraught with issues: the probe can randomly turn on and off, competes with light emitting from the cell, and often requires such intense laser excitation, it eventually destroys the probe, muddling anything you'd be interested in seeing.

"The nanoparticles we've designed can be used to study biomolecules one at a time," said Bruce Cohen, a staff scientist in the Biological Nanostructures Facility at Berkeley Lab's nanoscience research center, the Molecular Foundry. "These single-molecule probes will allow us to track proteins in a cell or around its surface, and to look for changes in activity when we add drugs or other bioactive compounds."

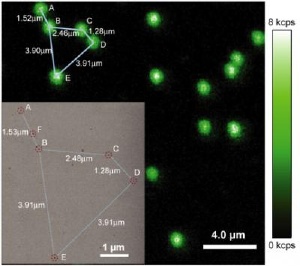

Molecular Foundry post-doctoral researchers Shiwei Wu and Gang Han, led by Cohen, Imaging and Manipulation of Nanostructures staff scientist Jim Schuck and Inorganic Nanostructures Facility Director Delia Milliron, worked to develop nanocrystals containing rare earth elements that absorb low-energy infrared light and transform it into visible light through a series of energy transfers when they are struck by a continuous wave, near-infrared laser. Biological tissues are more transparent to near-infrared light, making these nanocrystals well suited for imaging living systems with minimal damage or light scatter.

"Rare earths have been known to show phosphorescent behavior, like how the old-style television screen glows green after you shut it off. These nanocrystals draw on this property, and are a million times more efficient than traditional dyes," said Schuck. "No probe with ideal single-molecule imaging properties had been identified to date—our results show a single nanocrystal is stable and bright enough that you can go out to lunch, come back, and the intensity remains constant."

To study how these probes might behave in a real biological system, the Molecular Foundry team incubated the nanocrystals with embryonic mouse fibroblasts, cells crucial to the development of connective tissue, allowing the nanocrystals to be taken up into the interior of the cell. Live-cell imaging using the same near-infrared laser showed similarly strong luminescence from the nanocrystals within the mouse cell, without any measurable background signal.

"While these types of particles have existed in one form or another for some time, our discovery of the unprecedented 'single-molecule' properties these individual nanocrystals possess opens a wide range of applications that were previously inaccessible," Schuck adds.