Nov 13 2019

Scientists have created a new method to carry out optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the joints and other hard-to-reach areas of the human body.

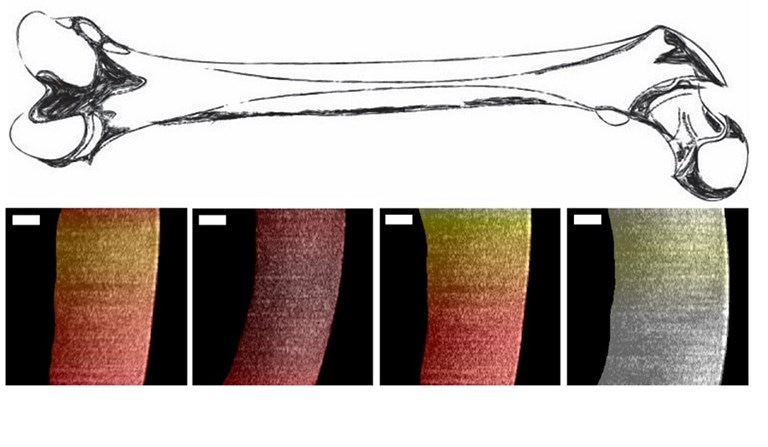

Researchers used a new endoscopic OCT system to visualize variances in pig cartilage thickness. The image shows a sketch of a femur and processed OCT images with thin regions shown in dark red and thicker regions more yellow and white. The scale bar is 250 microns. Image Credit: Evan T. Jelly, Duke University.

Researchers used a new endoscopic OCT system to visualize variances in pig cartilage thickness. The image shows a sketch of a femur and processed OCT images with thin regions shown in dark red and thicker regions more yellow and white. The scale bar is 250 microns. Image Credit: Evan T. Jelly, Duke University.

Thanks to the latest advancement, the high-resolution biomedical imaging method can be used in new medical and surgical applications.

The OCT technique can image structures that are quantified in microns, rendering it suitable for viewing even mild changes in tissues that may indicate damage or disease. Even though OCT is the standard of care in ophthalmology, it has been rather challenging to make a high-quality OCT device that is small enough to be used inside the body.

In Optics Letters, The Optical Society (OSA) journal, Duke University researchers reported how a rigid borescope—basically a thin tube of lenses—was used to transmit the infrared light required to perform the OCT. The borescope measures only 4 mm in diameter and makes the beam delivery parts of the instrument extremely thin without compromising on the imaging performance.

We saw a need for OCT image guidance in arthroscopic surgery, a minimally invasive procedure that uses an endoscope to address joint damage. We took the low-cost OCT imaging platform we previously developed and adapted it to meet the requirements of this application.

Evan T. Jelly, Research Team Leader, Duke University

OCT Through an Endoscope

In association with Adam Wax, Jelly and his research team earlier developed OCT systems that cost only a fraction of the price of conventional models.

To develop an OCT instrument that can be utilized to check the health of cartilage in a joint, the researchers built an endoscopic delivery system that employs a prototype stiff borescope to send the image from the tissue to a fiber optic connection.

The narrow front viewing section of the instrument enables it to access hard-to-reach cavities and structures that otherwise cannot be accessed with the larger part of the instrument that scans the patient.

The scientists developed the endoscopic OCT system to offer real-time quantitative data on the thickness of cartilage without requiring the physician to damage or cut the tissue. Such an analysis is crucial for osteoarthritis and similar painful joint conditions that manifest when cartilage wears down and turns out to be thinner.

To test the OCT system, the scientists used the device to measure the cartilage thickness in pig knees. Since the cartilage of humans and pigs is similar, this provided an initial idea of how the instrument would work in humans. The device was able to precisely detect the bone-cartilage interface for samples that had a thickness of less than 1.1 mm.

With additional development, the instrument can potentially enable clinicians to provide less invasive treatment for painful joint conditions.

But first, the scientists have to demonstrate that the OCT instrument can image thicker samples because the cartilage of humans is slightly thicker than that of pigs. Moreover, the team intends to further enhance the ergonomics for use at the time of surgery.

By developing a new portable, low-cost version of OCT, we show that the success of this imaging approach will no longer be limited to ophthalmology applications. With some engineering expertise, this OCT platform can be adapted to fit a wide range of clinical needs.

Evan T. Jelly, Research Team Leader, Duke University