Mar 26 2019

Modern analytical tools like mass spectrometers can identify many unknown substances, allowing scientists to easily tell whether foods or medicines have been altered. However, the cost, size, power consumption and complexity of these instruments often prevent their use in resource-limited regions. Now, in ACS Central Science, researchers report that they have developed a simple, inexpensive method to identify samples by seeing how they react to a change in their environment.

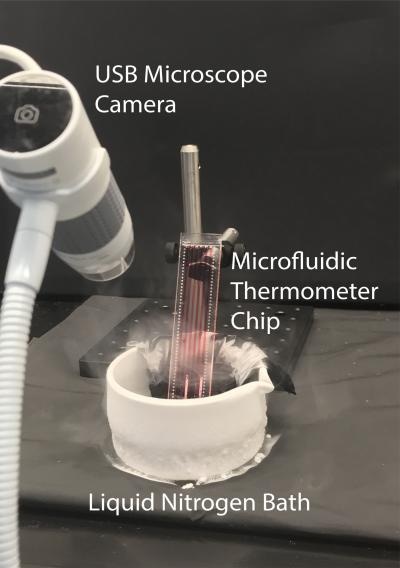

A new method identifies substances by examining how they change after being immersed in liquid nitrogen. Credit: American Chemical Society.

A new method identifies substances by examining how they change after being immersed in liquid nitrogen. Credit: American Chemical Society.

According to the World Health Organization, roughly 10 percent of all medicines in low- and middle-income countries are substandard or counterfeit. As with counterfeit medications, fraudulent foods can also place consumers at risk of illness or death, in addition to costing the industry billions of dollars per year. William Grover and colleagues at the University of California, Riverside wondered whether they could develop a simple, less expensive and reliable test to compare unknown samples with authentic foods and medicines. The researchers based their test on “chronoprints,” a term they use to describe images that capture how a sample changes over space and time in response to a perturbation –– in this case, a sudden temperature change.

The researchers loaded several liquid samples into long parallel channels on a microfluidic chip. Then, they immersed one end of the chip in liquid nitrogen, which created a temperature gradient that caused the samples to freeze, thaw, separate into components or otherwise change with time and distance away from the liquid nitrogen. With a USB camera, they captured videos of how the samples changed, converted these videos to images and compared the images using computer programs. The researchers found that identical samples, such as the same brand of cold medicine or extra-virgin olive oil, had very similar chronoprints, whereas adulterated medicine or olive oil did not. In principle, the method, which is much less expensive than current approaches, could also be used to analyze gases or dissolved solid samples, the researchers say.