Nov 21 2017

The vault-like, 40-foot diameter, 40-ton door of Chamber A at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston was unsealed on November 18, signaling the end of cryogenic testing for NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope.

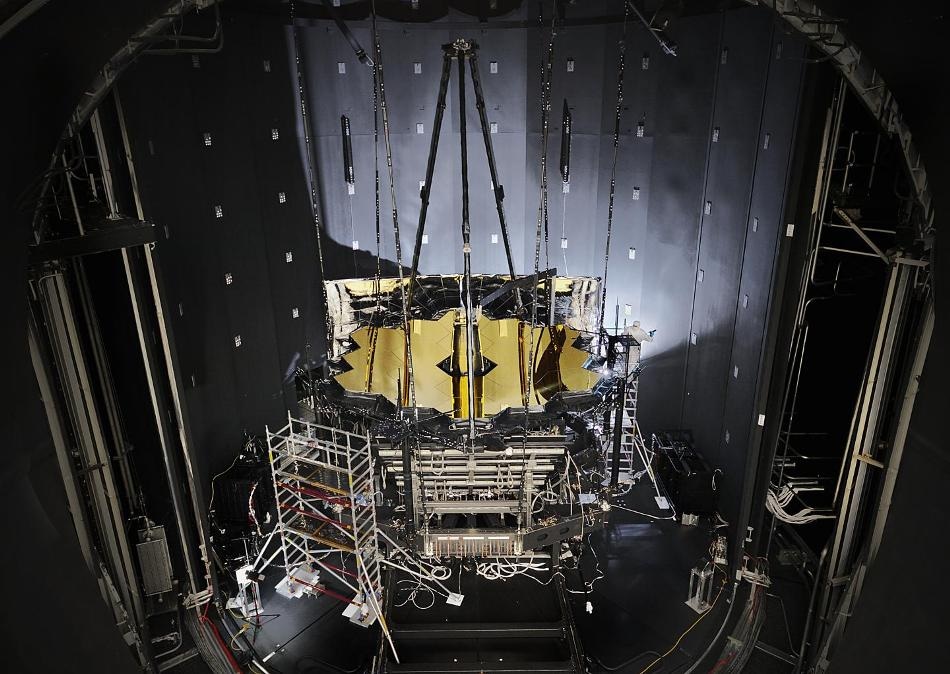

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope sits inside Chamber A at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston after having completed its cryogenic testing on Nov. 18, 2017. This marked the telescope's final cryogenic testing, and it ensured the observatory is ready for the frigid, airless environment of space. (Credit: NASA/Chris Gunn)

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope sits inside Chamber A at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston after having completed its cryogenic testing on Nov. 18, 2017. This marked the telescope's final cryogenic testing, and it ensured the observatory is ready for the frigid, airless environment of space. (Credit: NASA/Chris Gunn)

The historic chamber’s massive door opening brings to a close about 100 days of testing for Webb, a significant milestone in the telescope’s journey to the launch pad. The cryogenic vacuum test began when the chamber was sealed shut on July 10, 2017. Scientists and engineers at Johnson put Webb’s optical telescope and integrated science instrument module (OTIS) through a series of tests designed to ensure the telescope functioned as expected in an extremely cold, airless environment akin to that of space.

“After 15 years of planning, chamber refurbishment, hundreds of hours of risk-reduction testing, the dedication of more than 100 individuals through more than 90 days of testing, and surviving Hurricane Harvey, the OTIS cryogenic test has been an outstanding success,” said Bill Ochs, project manager for the James Webb Space Telescope at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “The completion of the test is one of the most significant steps in the march to launching Webb.”

These tests included an important alignment check of Webb’s 18 primary mirror segments, to make sure all of the gold-plated, hexagonal segments acted like a single, monolithic mirror. This was the first time the telescope’s optics and its instruments were tested together, though the instruments had previously undergone cryogenic testing in a smaller chamber at Goddard. Engineers from Harris Space and Intelligence Systems, headquartered in Melbourne, Florida, worked alongside NASA personnel for the test at Johnson.

“The Harris team integrated Webb’s 18 mirror segments at Goddard and designed, built, and helped operate the advanced ground support and optical test equipment at Johnson,” said Rob Mitrevski, vice president and general manager of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance at Harris. “They were a key, enabling part of the successful Webb telescope testing team.”

The Webb telescope team persisted with the testing even when Hurricane Harvey slammed into the coast of Texas on Aug. 25 as a category 4 hurricane before stalling over eastern Texas and weakening to a tropical storm, where it dropped as much as 50 inches of rain in and around Houston. Many Webb telescope team members at Johnson endured the historic storm, working tirelessly through overnight shifts to make sure Webb’s cryogenic testing was not interrupted. In the wake of the storm, some Webb team members, including team members from Harris, volunteered their time to help clean up and repair homes around the city, and distribute food and water to those in need.

“The individuals and organizations that have led us to this most significant milestone represent the very best of the best. Their knowledge, dedication, and execution to successfully complete the testing as planned, even while enduring Hurricane Harvey, cannot be overstated,” said Mark Voyton, James Webb Space Telescope optical telescope element and integrated science instrument manager at Goddard. “Every team member delivered critical knowledge and insight into the strategic and tactical planning and execution required to complete all of the test objectives, and I am honored to have experienced this phase of our testing with every one of them.”

Before cooling the chamber, engineers removed the air from it, which took about a week. On July 20, engineers began to bring the chamber, the telescope, and the telescope’s science instruments down to cryogenic temperatures — a process that took about 30 days. During cool down, Webb and its instruments transferred their heat to surrounding liquid nitrogen and cold gaseous helium shrouds in Chamber A. Webb remained at “cryo-stable” temperatures for about another 30 days, and on Sept. 27, the engineers began to warm the chamber back to ambient conditions (near room temperature), before pumping the air back into it and unsealing the door.

“With an integrated team from all corners of the country, we were able to create deep space in our chamber and confirm that Webb can perform flawlessly as it observes the coldest corners of the universe,” said Jonathan Homan, project manager for Webb’s cryogenic testing at Johnson. “I expect [Webb] to be successful, as it journeys to Lagrange point 2 [after launch] and explores the origins of solar systems, galaxies, and has the chance to change our understanding of our universe.”

While Webb was inside the chamber, insulated from both outside visible and infrared light, engineers monitored it using thermal sensors and specialized camera systems. The thermal sensors kept tabs on the temperature of the telescope, while the camera systems tracked the physical position of Webb to see how its components very minutely moved during the cooldown process. Monitoring the telescope throughout the testing required the coordinated effort of every Webb team member at Johnson.

“This test team spanned nearly every engineering discipline we have on Webb,” said Lee Feinberg, optical telescope element manager for the Webb telescope at Goddard. “In every area there was incredible attention to detail and great teamwork, to make sure we understand everything that happened during the test and to make sure we can confidently say Webb will work as planned in space.”

In space, the telescope must be kept extremely cold, in order to be able to detect the infrared light from very faint, distant objects. Webb and its instruments have an operating temperature of about 40 Kelvin (or about minus 387 Fahrenheit / minus 233 Celsius). Because the Webb telescope’s mid-infrared instrument (MIRI) must be kept colder than the other research instruments, it relies on a cryocooler to lower its temperature to less than 7 Kelvin (minus 447 degrees Fahrenheit / minus 266 degrees Celsius).

To protect the telescope from external sources of light and heat (like the Sun, Earth and Moon), as well as from heat emitted by the observatory, a five-layer, tennis court-sized sunshield acts like a parasol that provides shade. The sunshield separates the observatory into a warm, sun-facing side (reaching temperatures close to 185 degrees Fahrenheit / 85 degrees Celsius) and a cold side (minus 400 degrees Fahrenheit / minus 240 degrees Celsius). The sunshield blocks sunlight from interfering with the sensitive telescope instruments.

Webb’s combined science instruments and optics next journey to Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems in Redondo Beach, California, where they will be integrated with the spacecraft element, which is the combined sunshield and spacecraft bus. Together, the pieces form the complete James Webb Space Telescope observatory. Once fully integrated, the entire observatory will undergo more tests during what is called "observatory-level testing." This testing is the last exposure to a simulated launch environment before flight and deployment testing on the whole observatory.

Webb is expected to launch from Kourou, French Guiana, in the spring of 2019.

The James Webb Space Telescope, the scientific complement to NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, will be the premier space observatory of the next decade. Webb is an international project led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and CSA (Canadian Space Agency).

For more information about the Webb telescope visit: www.webb.nasa.gov or www.nasa.gov/webb