Sep 25 2014

Astronomers using data from three of NASA's space telescopes -- Hubble, Spitzer, and Kepler -- have discovered clear skies and steamy water vapor on a gaseous planet outside our solar system. The planet is about the size of Neptune, making it the smallest for which molecules of any kind have been detected.

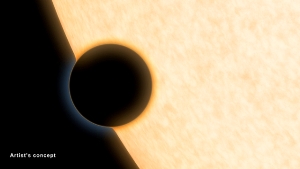

A Neptune-size planet with a clear atmosphere is shown crossing in front of its star in this artist's depiction. Such crossings, or transits, are observed by telescopes like NASA's Hubble and Spitzer to glean information about planets' atmospheres. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

A Neptune-size planet with a clear atmosphere is shown crossing in front of its star in this artist's depiction. Such crossings, or transits, are observed by telescopes like NASA's Hubble and Spitzer to glean information about planets' atmospheres. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

"The discovery is a significant milepost on the road to eventually analyzing the atmospheric composition of smaller, rocky planets more like Earth," said John Grunsfeld, assistant administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. "Such achievements are only possible today with the combined capabilities of these unique and powerful observatories."

Clouds in the atmospheres of planets can block the view to underlying molecules that reveal information about the planets' compositions and histories. Finding clear skies on a Neptune-size planet is a good sign that smaller planets might have similarly good visibility.

"When astronomers go observing at night with telescopes, they say 'clear skies' to mean good luck," said Jonathan Fraine of the University of Maryland, College Park, lead author of a new study appearing in Nature. "In this case, we found clear skies on a distant planet. That's lucky for us because it means clouds didn't block our view of water molecules."

The planet, HAT-P-11b, is a so-called exo-Neptune -- a Neptune-size planet that orbits another star. It is located 120 light-years away in the constellation Cygnus. Unlike our Neptune, this planet orbits closer to its star, making one lap roughly every five days. It is a warm world thought to have a rocky core and gaseous atmosphere. Not much else was known about the composition of the planet,or other exo-Neptunes like it, until now.

Part of the challenge in analyzing the atmospheres of planets like this is their size. Larger, Jupiter-like planets are easier to see because of their impressive girth and relatively puffy atmospheres. In fact, researchers have already been able to detect water vapor in those planets. Smaller planets are more difficult to probe, and what's more, the ones observed to date all appeared to be cloudy.

In the new study, astronomers set out to look at the atmosphere of HAT-P-11b, not knowing if its weather would call for clouds or not. They used Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3, and a technique called transmission spectroscopy, in which a planet is observed as it crosses in front of its parent star. Starlight filters through the rim of the planet's atmosphere and into a telescope's lens. If molecules like water vapor are present, they absorb some of the starlight, leaving distinct signatures in the light that reaches our telescopes.

Using this strategy, Hubble was able to detect water vapor in HAT-P-11b. This technique indicates the planet did not have clouds blocking the view, a hopeful sign that more cloudless planets can be located and analyzed in the future.

But before the team could celebrate clear skies on the exo-Neptune, they had to show that starspots -- cooler "freckles" on the face of stars -- were not the real sources of water vapor. Cool starspots on the parent star can contain water vapor that might appear erroneously to be from the planet. That's when the team turned to Kepler and Spitzer. Kepler had been observing one patch of sky for years, and HAT-P-11b happens to lie in the field. Those visible-light data were combined with targeted Spitzer observations taken at infrared wavelengths. By comparing these observations, the astronomers figured out that the starspots were too hot to have any steam.

It was at that point the team could celebrate detecting water vapor on a world unlike any in our solar system. "We think that exo-Neptunes may have diverse compositions, which reflect their formation histories," said Heather Knutson of the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, co-author of the new study. "Now with data like these, we can begin to piece together a narrative for the origin of these distant worlds."

The results from all three telescopes demonstrate that HAT-P-11b is blanketed in water vapor, hydrogen gas, and likely other yet-to-be-identified molecules. Theorists will be drawing up new models to explain the planet's makeup and origins.

"We are working our way down the line, from hot Jupiters to exo-Neptunes," said Drake Deming, a co-author of the study also from University of Maryland, College Park. "We want to expand our knowledge to a diverse range of exoplanets."

The astronomers plan to examine more exo-Neptunes in the future, and hope to apply the same method to smaller super-Earths -- the massive, rocky cousins to our home world with up to 10 times the mass. Our solar system doesn't have a super-Earth, but NASA's Kepler mission is finding them around other stars in droves. NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in 2018, will search super-Earths for signs of water vapor and other molecules; however, finding signs of oceans and potentially habitable worlds is likely a ways off.

"The work we are doing now is important for future studies of super-Earths and even smaller planets, because we want to be able to pick out in advance the planets with clear atmospheres that will let us detect molecules," said Knutson.

Once again, astronomers will be crossing their fingers for clear skies.

More information about this study, Hubble, Kepler and Spitzer is online at:

http://hubblesite.org/news/2014/42

http://www.nasa.gov/

http://www.spacetelescope.org/heic1420/

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and the European Space Agency. NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., in Washington.