Jul 24 2014

A research team from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), working with the Cleveland Clinic, has demonstrated a dramatically improved technique for analyzing biological cells and tissues based on characteristic molecular vibration "signatures."

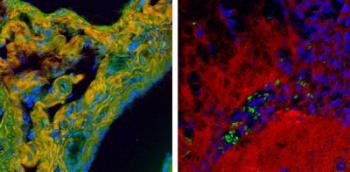

High-speed BCARS allows detailed mapping of specific components of tissue samples. A false-color BCARS image of mouse liver tissue (left) picks out cell nuclei in blue, collagen in orange and proteins in green. An image of tumor and normal brain tissue from a mouse (right) has been colored to show cell nuclei in blue, lipids in red and red blood cells in green. Images show an area about 200 micrometers across. (Credit: Camp/NIST)

High-speed BCARS allows detailed mapping of specific components of tissue samples. A false-color BCARS image of mouse liver tissue (left) picks out cell nuclei in blue, collagen in orange and proteins in green. An image of tumor and normal brain tissue from a mouse (right) has been colored to show cell nuclei in blue, lipids in red and red blood cells in green. Images show an area about 200 micrometers across. (Credit: Camp/NIST)

The new NIST technique is an advanced form of the widely used spontaneous Raman spectroscopy, but one that delivers signals that are 10,000 times stronger than obtained from spontaneous Raman scattering, and 100 times stronger than obtained from comparable "coherent Raman" instruments, and uses a much larger portion of the vibrational spectrum of interest to cell biologists.*

The technique, a version of "broadband, coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering" (BCARS), is fast and accurate enough to enable researchers to create high-resolution images of biological specimens, containing detailed spatial information on the specific biomolecules present at speeds fast enough to observe changes and movement in living cells, according to the NIST team.

Raman spectroscopy is based on a subtle interplay between light and molecules. Molecules have characteristic vibration frequencies associated with their atoms flexing and stretching the molecular bonds that hold them together. Under the right conditions, a photon interacting with the molecule will absorb some of this energy from a particular vibration and emerge with its frequency shifted by that frequency—this is "anti-Stokes scattering." Recording enough of these energy-enhanced photons reveals a characteristic spectrum unique to the molecule. This is great for biology because in principle it can identify and distinguish between many complex biomolecules without destroying them and, unlike many other techniques, does not alter the specimen with stains or fluorescent or radioactive tags.

Using this intrinsic spectral information to map specific kinds of biomolecules in an image is potentially very powerful, but the signal levels are very faint, so researchers have worked for years to develop enhanced methods for gathering these spectra.** "Coherent" Raman methods use specially tuned lasers to both excite the molecular vibrations and provide a bright source of probe photons to read the vibrations. This has partially solved the problem, but the coherent Raman methods developed to date have had limited ability to access most of the available spectroscopic information.

Most current coherent Raman methods obtain useful signal only in a spectral region containing approximately five peaks with information about carbon-hydrogen and oxygen-hydrogen bonds. The improved method described by the NIST team not only accesses this spectral region, but also obtains excellent signal from the "fingerprint" spectral region, which has approximately 50 peaks—most of the useful molecular ID information.

The NIST instrument is able to obtain enhanced signal largely by using excitation light efficiently. Conventional coherent Raman instruments must tune two separate laser frequencies to excite and read different Raman vibration modes in the sample. The NIST instrument uses ultrashort laser pulses to simultaneously excite all vibrational modes of interest. This "intrapulse" excitation is extremely efficient and produces its strongest signals in the fingerprint region. "Too much light will destroy cells," explains NIST chemist Marcus Cicerone, "So we've engineered a very efficient way of generating our signal with limited amounts of light. We've been more efficient, but also more efficient where it counts, in the fingerprint region."

Raman hyperspectral images are built up by obtaining spectra, one spatial pixel at a time. The hundred-fold improvement in signal strength for the NIST BCARS instrument makes it possible to collect individual spectral data much faster and at much higher quality than before—a few milliseconds per pixel for a high-quality spectrum versus tens of milliseconds for a marginal quality spectrum with other coherent Raman spectroscopies, or even seconds for a spectrum from more conventional spontaneous Raman instruments. Because it's capable of registering many more spectral peaks in the fingerprint region, each pixel carries a wealth of data about the biomolecules present. This translates to high-resolution imaging within a minute or so whereas, notes NIST electrical engineer Charles Camp, Jr., "It's not uncommon to take 36 hours to get a low-resolution image in spontaneous Raman spectroscopy."

"There are a number of firsts in this paper for Raman spectroscopy," Camp adds. "Among other things we show detailed images of collagen and elastin—not normally identified with coherent Raman techniques—and multiple peaks attributed to different bonds and states of nucleotides that show the presence of DNA or RNA."