Jun 5 2013

A four-university collaboration that includes Lehigh University astrophysicist Joshua Pepper has discovered a hot Saturn-like planet in another solar system 700 light years away.

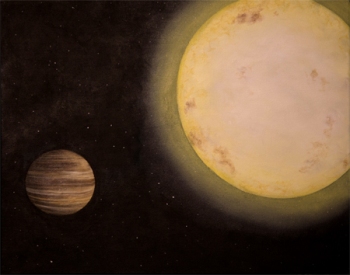

An artist's rendering of exoplanet KELT-6b by Lexington, KY-based artist Erin Plew of Queen of Arts LLC.

An artist's rendering of exoplanet KELT-6b by Lexington, KY-based artist Erin Plew of Queen of Arts LLC.

The discovery came with the aid of inexpensive ground-based telescopes, the luck of clear skies on the right nights and a combination of creative methods to detect planetary orbits.

The discovery of exoplanet KELT-6b was announced at the American Astronomical Society’s national meeting in Indianapolis on June 4, 2013.

As seen from Earth, KELT-6b resides in the constellation Coma Berenices, near Leo, and has an orbit that crosses, or “transits,” in front of its star every 7.8 days. That means a “year” on the planet lasts just over a week, and its trip across the face of its star as seen from Earth lasts only seven hours.

Seven hours seems like a short time, but most planets found by ground-based telescopes have had even shorter transits. Catching a complete observation of KELT-6b took more luck–seven hours of continuous telescope time with clear skies during darkness at the University of Louisville’s Moore Observatory.

KELT-6b is now the longest-duration, full planetary transit continuously observed from the ground, according to Louisville’s Karen Collins, a doctoral student and the paper’s lead author. This is the 4th planet discovered by the KELT project.

KELT stands for the Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope project, jointly operated by Pepper and astronomers at The Ohio State University and Vanderbilt University. The KELT-North telescope in Arizona and its twin, KELT-South in South Africa, are no more powerful than high-end digital cameras. The KELT telescopes record images of huge swaths of the night sky. Scientists search for slight, periodic dimming of any stars in the images, which could indicate a planet transiting its star. Once the slight variation in light is detected, scientists use larger telescopes to determine exactly which star is affected and precisely how much it dims. While KELT-North briefly glimpsed the new planet last year, the team needed help with follow-up observations to capture the entire transit, explained Scott Gaudi, associate professor of astronomy at Ohio State and member of the KELT team.

Pepper, an assistant professor of physics at Lehigh, conducts the bulk of his research on the discovery of new planets, a field he says is crowded with scientists and expensive, internationally-funded telescopes. But as a graduate student at Ohio State, he began to theorize of a cheaper, quicker way to isolate planets that were good prospects for intense study.

With assistance, he planned and built the first KELT telescope as a graduate student.

“These are the smallest, cheapest telescopes out there,” said Pepper. “But our goal is not to find a lot of planets using this method. The few we do find, however, are orbiting extremely bright host stars, making them prime targets for future research using the big telescopes in Hawaii, Chile and space.”

Using the fully robotic telescope, the team scans about 1.5 million available stars, 1200-1500 times a year, looking for that sudden dip in brightness that indicates an eclipsing—although the proper term is a “transiting”— planet. The team then analyzes the data over long periods of time, looking for that tiny 1 percent dip in brightness that indicates a planet is passing by.

The planets they find most often are called Hot Jupiters, huge gas giants so close to a star they take only 3-8 days to orbit. Mercury, for example, needs 88 days to orbit our Sun, meaning there is little possibility of life on any of KELT’s discoveries.

“These are planets whose atmospheres we can observe,” says Pepper. “Now that they are discovered, future research will analyze starlight as it filters through the planet’s atmosphere during transit, revealing the gases that make up the planet.”

Several different observational techniques and calculations combined to reveal that KELT-6b is a hot gas-giant planet orbiting a star about the same age as our sun. The planet resembles our own Saturn in terms of size and mass—though it has no rings. It also resembles the most studied exoplanet to date, HD 209458b, but differs because it was formed in an environment low in elements heavier than hydrogen and helium. By comparing the newly discovered planet with others, scientists can learn more about planetary atmospheres and the evolution of planetary systems.

Along with Collins, Pepper, and Gaudi, other leaders of the team on this discovery included Keivan Stassun, professor of physics and astronomy and Robert Siverd, staff scientist, both with Vanderbilt University; John Kielkopf, professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Louisville, and Jason Eastman, a postdoctoral fellow at Las Cumbres Observatory.

Additional funding for the work came from the National Science Foundation, NASA, and Vanderbilt University.