Jul 11 2019

Organic light-emitting diodes, or OLEDs, for short, are currently used in various electronic devices meant for display applications, spanning from televisions to smartphones.

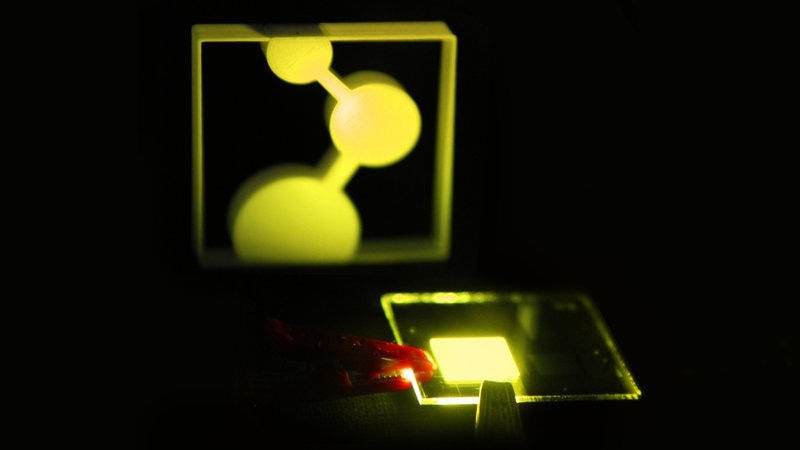

The first prototype of the OLED developed in Mainz illuminates the MPI-P logo (Image credit: MPI-P)

The first prototype of the OLED developed in Mainz illuminates the MPI-P logo (Image credit: MPI-P)

At the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research (MPI-P), researchers have now successfully developed a novel design for these kinds of LEDs. The team was able to reduce the number of varied layers making up an OLED to just a single one.

In the coming days, this could allow the use of inkjet printer to print light-emitting diodes. The first model of the developed light-emitting diode can already compete with existing OLEDs available on the market, in terms of efficiency and luminosity.

OLEDs are components that contain the so-called organic compounds in which carbon is the primary component, and they no longer include compounds containing the semiconducting material gallium. However, compared to traditional light-emitting diodes, the lifetime and luminosity of OLEDs are presently lower, which is why they are in the forefront of today’s field of research.

Now, a research team at the MPI-P, headed by group leader Gert-Jan Wetzelaer (Department of Professor Paul Blom) has come up with a novel OLED concept. At present, OLEDs is made up of numerous wafer-thin layers. While a few layers are utilized to transport charges, others are used to efficiently add electrons within the active layer in which light is produced.

Therefore, existing OLEDs can easily include five to seven layers. Furthermore, the team has now created an OLED, which contains just a single layer and this is supplied with electricity through two electrodes. This approach not only eases the fabrication of such OLED but may also lead to the development of printable displays.

Using the first prototype, the Mainz team successfully demonstrated that a brightness of the emitted light of 10,000 candela/m2 can be generated with a voltage of just 2.9 V—this corresponds to roughly 100 times the luminosity of contemporary screens.

This is a record for existing OLEDs because such high luminosity was achieved at very low voltage. In addition, the researchers were able to determine an external efficiency of 19%, meaning that 19% of the electrical energy supplied is changed into light that emerges in the direction of the viewer. With this value, the OLED prototype can also compete with today’s OLEDs comprising five or even more numbers of layers.

In continuous operation, the investigators measured a so-called LT50 lifetime of nearly 2000 hours at a brightness corresponding to 10 times that of contemporary displays. The initial luminosity, within this time, has dropped to half of its value.

For the future, we hope to be able to improve the concept even further and thus achieve even longer lifetimes. This means that the concept could be used for industrial purposes.

Dr Gert-Jan Wetzelaer, Group Leader, Department of Molecular Electronics, Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research

The researchers believe that their recently developed single-layer concept—that is, the reduced OLED complexity—will help in identifying and improving the processes accountable for reduced luminance over time.

The researchers are utilizing a light-emitting layer based on what is known as “Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence” (TADF). Although this physical principle was known for many years, it became the focus of OLED studies approximately a decade ago, following a demonstration in Japan in which electrical energy was efficiently converted into light.

Since that time, scientists have been working to create TADF-based OLEDs, because these eliminate the need for costly molecular complexes composed of rare-earth metals that are being utilized in today’s OLEDs.

The scientists have published the results of the study in the prestigious journal, Nature Photonics.