Aug 19 2008

Cancer surgeons today operate "blind" with no clear way of determining in real-time whether they have removed all of the diseased tissue, which is the key to successful surgery. Researchers in Massachusetts now report development and early clinical trials of a new imaging system that highlights cancerous tissue in the body so that surgeons can more easily see and remove diseased tissue with less damage to normal tissue near the tumor.

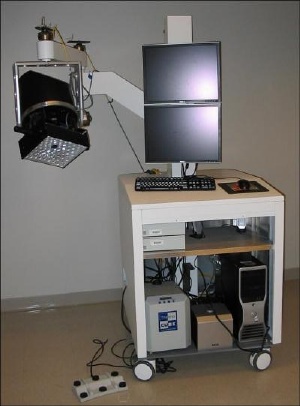

The Fluorescence-Assisted Resection and Exploration (FLARE) device. Credit: John V. Frangioni, M.D., Ph.D. Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

The Fluorescence-Assisted Resection and Exploration (FLARE) device. Credit: John V. Frangioni, M.D., Ph.D. Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

The technique shows particular promise for improving surgery for breast, prostate, and lung cancer, whose tumor boundaries can be difficult to track at advanced stages, they say. Described today at the 236th National Meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS), the technique can also help cancer surgeons avoid cutting critical structures such as blood vessels and nerves.

"This technique is really the first time that cancer surgeons can see structures that are otherwise invisible, providing true image-guided surgery," says project director John Frangioni, M.D., Ph.D., of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston and co-director of its Center for Imaging Technology and Molecular Diagnostics. "If we're able to see cancer, we have a chance of curing it."

The system is called FLARE, or Fluorescence-Assisted Resection and Exploration. Under development for the past decade, the portable system consists of a near-infrared (NIR) imaging system, a video monitor, and a computer. "The system has no moving parts, uses LEDs instead of lasers for excitation, makes no contact with the patient, and is sterile," Frangioni says.

The unique system uses special chemical dyes, called NIR fluorophores, that are designed to target specific structures such as cancer cells when the dyes are injected into patients. When exposed to NIR light, which is invisible to the human eye, the dyes or contrast agents light up the cancer cells and are shown on a video monitor. Images of these "glowing" cancer cells are then superimposed over images of the normal surgical field, allowing surgeons to easily see the cancer cells even in a background crowded by blood and other anatomical structures, the researcher says.

Frangioni compares the system to the old color-by-number paint sets. Instead of coloring by numbers, it will provide surgeons with a means of "cutting by color," he says. The computerized technique also gives physicians the power to control multiple viewing angles and different magnification levels through the use of a footswitch.

In preliminary studies, Frangioni and colleagues used the FLARE to successfully visualize organs and body fluids of mice and map the lymph nodes of pigs, all in real-time. The first human clinical trials, expected to begin this summer, involve mapping the lymph nodes of a small group of patients with breast cancer. Broader clinical use of the device could occur within five years, the researchers estimate.

In the future, fluorophores could be developed to highlight nerves and blood vessels in one color while visualizing cancer cells in a different color, allowing multiple structures to be viewed easily and even simultaneously, he says.

"The future of the technology now is really in the chemistry," Frangioni says. "We have to develop agents for specific tumors, nerves or blood vessels we're trying to visualize."

The study is funded primarily through a Bioengineering Research Partnership from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health.