Mar 1 2013

Researchers at Rice University and Sandia National Laboratories have made a nanotube-based photodetector that gathers light in and beyond visible wavelengths. It promises to make possible a unique set of optoelectronic devices, solar cells and perhaps even specialized cameras.

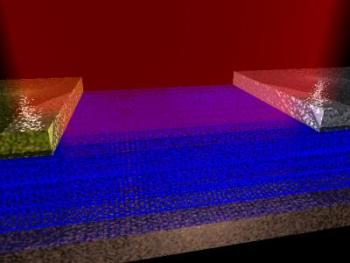

This illustration shows an array of parallel carbon nanotubes 300 micrometers long that are attached to electrodes and display unique qualities as a photodetector, according to researchers at Rice University and Sandia National Laboratories. Credit: Sandia National Laboratories

This illustration shows an array of parallel carbon nanotubes 300 micrometers long that are attached to electrodes and display unique qualities as a photodetector, according to researchers at Rice University and Sandia National Laboratories. Credit: Sandia National Laboratories

A traditional camera is a light detector that captures a record, in chemicals, of what it sees. Modern digital cameras replaced film with semiconductor-based detectors.

But the Rice detector, the focus of a paper that appeared today in the online Nature journal Scientific Reports, is based on extra-long carbon nanotubes. At 300 micrometers, the nanotubes are still only about 100th of an inch long, but each tube is thousands of times longer than it is wide.

That boots the broadband detector into what Rice physicist Junichiro Kono considers a macroscopic device, easily attached to electrodes for testing. The nanotubes are grown as a very thin "carpet" by the lab of Rice chemist Robert Hauge and pressed horizontally to turn them into a thin sheet of hundreds of thousands of well-aligned tubes.

They're all the same length, Kono said, but the nanotubes have different widths and are a mix of conductors and semiconductors, each of which is sensitive to different wavelengths of light. "Earlier devices were either a single nanotube, which are sensitive to only limited wavelengths," he said. "Or they were random networks of nanotubes that worked, but it was very difficult to understand why."

"Our device combines the two techniques," said Sébastien Nanot, a former postdoctoral researcher in Kono's group and first author of the paper. "It's simple in the sense that each nanotube is connected to both electrodes, like in the single-nanotube experiments. But we have many nanotubes, which gives us the quality of a macroscopic device."

With so many nanotubes of so many types, the array can detect light from the infrared (IR) to the ultraviolet, and all the visible wavelengths in between. That it can absorb light across the spectrum should make the detector of great interest for solar energy, and its IR capabilities may make it suitable for military imaging applications, Kono said. "In the visible range, there are many good detectors already," he said. "But in the IR, only low-temperature detectors exist and they are not convenient for military purposes. Our detector works at room temperature and doesn't need to operate in a special vacuum."

The detector is also sensitive to polarized light and absorbs light that hits it parallel to the nanotubes, but not if the device is turned 90 degrees.

The work is the first successful outcome of a collaboration between Rice and Sandia under Sandia's National Institute for Nano Engineering program funded by the Department of Energy. François Léonard's group at Sandia developed a novel theoretical model that correctly and quantitatively explained all characteristics of the nanotube photodetector. "Understanding the fundamental principles that govern these photodetectors is important to optimize their design and performance," Léonard said.

Kono expects many more papers to spring from the collaboration. The initial device, according to Léonard, merely demonstrates the potential for nanotube photodetectors. They plan to build new configurations that extend their range to the terahertz and to test their abilities as imaging devices. "There is potential here to make real and useful devices from this fundamental research," Kono said.